"Do you trust me?"

I have an absurdly long, rambling draft (well, multiple, actually) of an essay

discussing my observations and associated frustration with the inexpressiveness

of the English language.1 An illustrative example of one phenomenon that I

discuss in that essay, which has been the source of much frustration for me over

the years, is the titular question:

I find the word trust to be particularly fraught when used in a professional

and/or pseudo-professional setting, as the different meanings of the word

trust are easily conflated.

"Define trust…"

If we look at trust in the dictionary, we begin to see the

problem, as there are multiple, different, plausible options:

As a noun

assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of

someone or something

As a verb

to rely on the truthfulness or accuracy of : BELIEVE

and if we look at BELIEVE:

to consider to be true or honest

OR

to place confidence in : rely on

Using those definitions, we can project the original question into (at least)

two more expressive options, one or both of which may be what is intended by

the person asking.

- Do you believe I am behaving in good faith, with good intentions,

and sincerely doing my best?

- Do you have confidence in my context-relevant abilities?

The most common response when attempting to tease out this nuance in

conversation is resistance to even acknowledging that there are distinct senses

of the question. A surprising (to me) number of people seem to believe that the

answer to the second implicitly, necessarily matches answer to the first.

And, yet, I regularly encounter situations where my answer to one of the

questions for a particular individual in a particular context is "yes" while

the other is "no".2

An illustration

Consider the popular team building exercise of trust falls. In

high school, I worked at a summer camp which also had one of those ropes courses

that offer facilitated team building sessions. As a part of being staff at the

camp, we were divided into groups and went through a multi-day session,

including trust falls. In this particular case, there were two versions of the

trust fall.

For the first, all team members are standing on the ground and members take

turns falling backwards and being caught by one or two teammates standing

nearby ready to catch them.

For the second, the person falling stands an a platform six feet above the

ground and falls backward into a group of teammates, arranged in two rows facing

one another, with arms outstretched ready to catch the faller.

The first version of this is fairly low risk and harmless, barring a gross

size imbalance, even if a teammate in the catching role falters. The second,

however, presents a more substantial challenge for some of us.

By 16, I was larger than most of my peers at 6'2" at 225 lbs, particularly

compared to the rest of my cohort that day, which included a flyer on a local

cheer squad, who was at least a foot shorter than me and half my weight (or

less).

While I fully trusted the good intentions of my cohort and believed they

sincerely intended to do their best, the readily observable facts about their

relative size and strength—based on observing them working through the

more individual components of the course—undermined my confidence in their

ability to actually catch me in a way that was safe for everyone. And, of

course, I wouldn't be sharing this anecdote as an example if that skepticism

had not been borne out. Rather than actually catch me in the way that we had

caught everyone else, they merely managed to break my fall enough to prevent

injury.

"Presume good intent."

The most common breakdown I've observed in professional settings related to this

arises when an individual or group expresses skepticism or feeling uneasy about

a course of action and they are admonished to "Presume good intent," or "Give

the benefit of the doubt," or "Show some trust," or similarly pithy and

dismissive response rather than engaging the uneasy individual with curiosity.

In my experience, such responses always exacerbate the uneasy feelings.

The problems with these responses are twofold. Such responses often stem

from confusing an expression of low or uncertain confidence in a person's

skill for an expression of belief that the person is behaving in bad faith.

Responses emphasizing goodness of character or sincerity of

intention cannot reassure a lack of confidence in skill or ability.

In the rare case where the expressed concerns are about insincerity of

intentions, responding with admonishment signals that the skeptic's perspective

is considered worthless, which, if true, is a poor basis for future

collaboration.

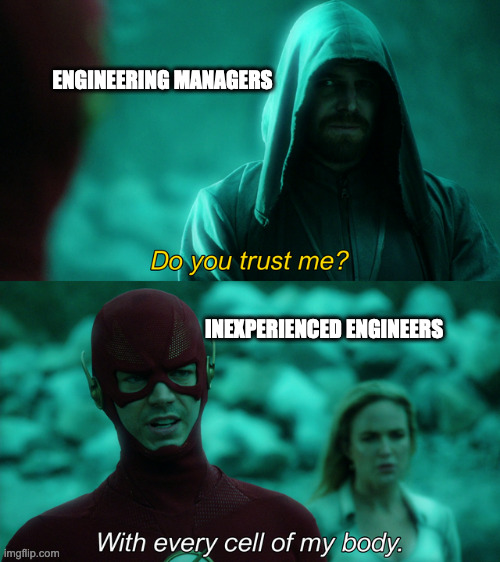

Accounting for (contextual) power dynamics

A common mistake made by managers (including executives) is that they believe

they're entitled to trust from anyone beneath them in the

organizational hierarchy. Managers do, of course, wield power, including the

right to make certain decisions, which, in turn, implies a reasonable

expectation of deference. But such deference does not imply trust in either of

the above senses.

Teams led by managers who misunderstand the difference between compulsory

deference and genuine trust (in either sense) tend to be brittle and crumble

quickly when they encounter adversity because they tend to require high-overhead

coordination, which is inherently slower to adapt to changing circumstances.

Managers who haven't earned trust in one or both senses are also much less

likely to benefit from informal support from team members, which is critical

in organizations working on complex, dynamic (read: interesting) problems.

It may take some managers a bit to recognize this organically, particularly if

their early management experience was in an organization where they'd already

established a baseline of trust. As noted above, managers undermine their cause

by responding to a perceived lack of trust with exhortations rather than seeking

understanding with genuine curiosity. If that exhortation is particularly

strident, they risk completely alienating team members who may look to leave

their team or the company.