Thoughts on Operational Responsibility [for Software Engineers]

I originally drafted this in 2014/2015 to help frame a

conversation around software engineers being on call. The primary audience was a

group of software engineers coming from a predominantly desktop software

background who believed they should not be on call. This memo was one component

of a very long conversation. This version has been lightly edited to elide

some contextual specifics.

Who is responsible for this?!

re·spon·si·ble: being the primary cause of something and so able to be

blamed or credited for it.

What happens when an application running in production starts failing at 2am on

Saturday? Do we wait until 8am Monday to fix it? Should someone be woken up to

address the problem? Who should we wake up if the acute problem is that the

application has started crushing the database server by fetching a set of data

from a SQL database row by agonizing row via an ORM that encourages

engineers to reason about iterating over a list of things backed by an

abstracted-away SQL database in the same way they reason about lists of items in

memory? Applications fail as a result of ineffective or surprising changes to

application code at least as often as they fail because of underlying

network/hardware/etc failures.

<!-- prettier-ignore -->

Figuring out who to blame or even the notion that anyone is "to

blame" is not, it turns out, particularly useful. When an application is

materially broken in production, the most useful action is to rapidly identify,

assemble, and deploy the group of people who are best equipped to resolve the

problem.

Highly empowered software engineers

At [this company], engineers have a very high degree of functional

authority over production applications. A relatively large number of engineers

have direct access to our production systems with broad permissions.1

Developers deploy their applications when it suits them. Developers generally

have a high degree of influence in choosing which subsystem technologies their

applications use.

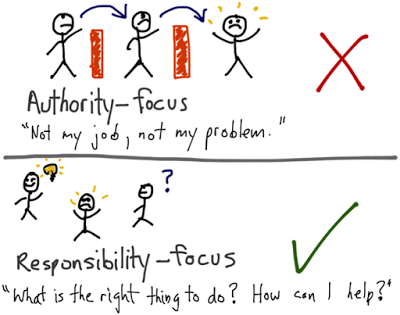

Broad access to production and the freedom to write and deploy applications

without first seeking approval from Ops, however, has not automatically resulted

in engineers expressing a commensurate sense of responsibility for the overall

health and functioning of their running applications and/or for the entire

production system.

With great power comes great responsibility

re·spon·si·ble: having an obligation to do something, or having control over

or care for someone, as part of one's job or role.

2

2

When we acknowledge that Ops and Development are corporately responsible for

the health and functioning of production applications, our focus can shift to

the question of how to better work together before, during, and after

applications are deployed to production and delivered to customers.

What does operational responsibility look like, practically, for an engineer?

- All engineers working on web applications or services, but particularly

those with production access, are expected to understand the production

environment itself and effectively wield the tools used to monitor and

manage the overall health of applications and services in production. This

includes making sure that the alerting systems are reasonably configured to

minimize false alarms

- Developers must understand the demands their application will place on

resources and collaborate with Operations to prepare and maintain a healthy

production environment. This includes capacity planning.

- For any web application or web service, there is an engineer with production

access available 24/7 to deal with issues related to their application–even

if that application doesn't have a 24/7 SLA.3

- That engineer is configured to receive via an interruptive channel all

appropriate and necessary alarms and notifications related to application

health during those times when they are scheduled to be available. As an

organization, we should minimize the number of people expected to be

available 24/7 365 days a year.4

- All engineers with production access make contact information available

(cell phone or functional equivalent) to Ops and other Development teams.

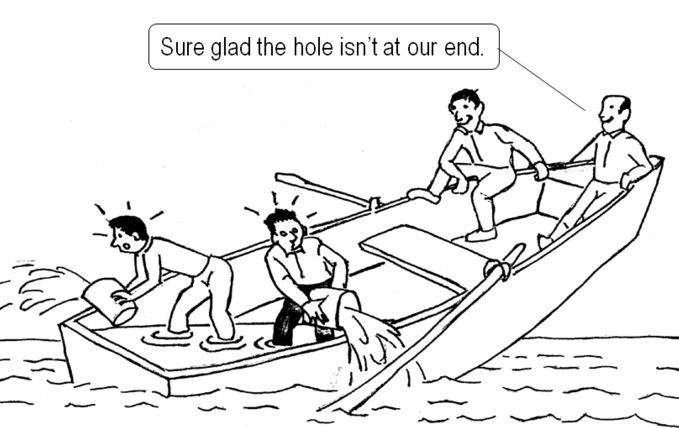

What if I get an alert, and it turns out to be a network/disk/hardware problem I can't personally solve? Can I just go back to bed?

If the other responders say, "We've got this, go back to bed", sure.

Otherwise, roll up your sleeves and figure out how to help. When things are

broken in a material way, the goal isn't to return you, individually, back to

your regularly scheduled activity (in this case, sleep). The goal is to get the

organization's systems and services back to an acceptable state. Everyone gets

back to normal the sooner this occurs; in the meantime, help.

Maybe the solution to the problem isn't to wait for the existing underlying

subsystem to be fixed. Maybe instead you can work to get your application spun

up on alternative gear. Maybe your application is up and running but another

team is struggling and could use a hand—lend it. Volunteer to transcribe status

updates via the appropriate communication channels.

Now, there will definitely be situations where there isn't anything you can help

with. That's fine. When that happens, confirm that there isn't any other way for

you to be helpful, let them know how to get ahold of you when/if your help is

needed and go back to your regularly scheduled activities.

Language, architecture, code structure, code style rules, method naming,

exception handling approaches, pattern choices, testing methodologies, and

development/test environment setup are all be tools in service of producing

reliable, performant, operable, production software in production which

delivers value to customers.

<!-- prettier-ignore -->

Other ideas related to this that deserve more attention at a later date

- Use the same tools/subsystems in development and test as you do in

production.

- Simplify your tool chain and the set of subsystems you use as an

organization.

- Prefer discoverable, explicit patterns over magical ones.

- Avoid dependency injection auto-wiring and don't configure dependency

injection externally unless absolutely necessary.

- Use AOP judiciously—it often obfuscates the source of system behavior.

- Be wary of tools that promise to abstract away your need to understand

the behavior of the abstracted away subsystems (e.g. heavyweight ORMs).

See Also

<!-- prettier-ignore-start -->

<!-- prettier-ignore-end -->